The Escalante liberals were always a noisy bunch.

By the summer of 2019, the epicenter of public lands disputes had spent over two decades collecting an assortment of newcomers — government employees, refugees from urban California, environmental activists, grazing “experts,” and the Monkey Wrench Gang types.

Many of these came to Escalante because they saw the place as an untouched, pristine wilderness. Instead, they found it already occupied by Mormons and ranchers.

The blend of old and new could have been friendly, but it was not to be. Old-timers grew wary of the newcomers’ academic view of how the life-long residents should be living.

Through the 1990s, ranchers — now grazing inside an enormous national monument — found vigilantes had been blocking off roads, tearing down fences, and burning the ranchers’ shelters to the ground. In one instance, environmentalists swooped in on a helicopter to shout down a group of workers trying to excavate out the Pine Creek irrigation diversion. These newcomers were not friendly, nor did they appreciate the importance of local concerns, such as irrigation water.

Over the years, the press had also become a problem. Unable, or perhaps unwilling to persuade locals of the ranchers’ destruction of local lands, liberal activists had found a much more receptive audience abroad. Still a vocal minority, they learned to leverage the media. Since, locals have grown tired of outsiders speaking on their behalf. It even became more frequent to see news stories quoting Escalante residents the locals had never heard of.

“Who is this ‘Kelton’ that is representing ‘our’ community on the news?” Escalante resident Jared Woolsey wrote on Facebook in reference to a pro-monument news story in 2017. “Were you here over 20 years ago when the monument was announced (from Arizona) and devastated ‘our’ community?” Woolsey added it was difficult “constantly fighting outsiders who know more than us.”

Residents felt that even their own local paper had turned liberal since Erica Walz had purchased The Insider a few years earlier. “It’s too bad about The Insider,” lamented one Wayne County resident who had once written for the paper before it sold to Walz. “I don’t understand why she had to use the paper to fight the people on environmental issues.”

A World on Fire

In 2019, Garfield County commissioner Jerry Taylor directed a question at Elaine Baldwin. Once the mayor of Panguitch City, Elaine had served the community in several other capacities and still sits on Garfield’s Planning and Zoning committee.

“What does Garfield County need?” Taylor asked Baldwin.

“We need a new newspaper,” Baldwin answered without hesitation. In her view, the local paper was far too liberal to represent its readers and didn’t understand or respect local conservative values. Indeed, 80% of Garfield and Wayne County residents had voted for Donald Trump in 2016, even with third-party Utahn Evan McMullin in the race.

“In 50 years when people look back at our newspapers to see what was going on during our time, I don’t want them thinking all we cared about was the Bryce Canyon bird count and saving the three-toed frog,” Baldwin said, maybe with a touch of hyperbole.

In 2019, liberal forces were hard at work to increase their presence in Garfield County. In the fall, Escalante City held an election to fill three city council seats and the Democrats put forward one of their own to run against the three other Republican candidates. Even with an alleged bullet-voting scheme by some on the left, the Democratic candidate still only got about a quarter of the vote.

“That result surprised me,” newcomer AJ Martel said of the election results. “I had assumed, at least by vocal share, that Escalante was nearly 50% liberal.”

Baldwin, on the other hand, wasn’t as surprised. “It was always clear to me that people writing online and in the news didn’t actually represent how most locals think,” she said.

Still without representation in Escalante’s city council, local Democrats ramped up their efforts into 2020 with the help of Rural Utah Project, which had been successful at turning San Juan County blue through a major voter registration effort among the Navajo. Escalante resident Byron Ellis, who first came to Utah as a field organizer for Rural Utah Project, announced his campaign to run against Jerry Taylor for the county commission seat.

By the middle of 2020, America’s political scene was officially on fire. The pandemic had upended society and soon it was only acceptable to engage with other humans if you were protesting social injustice in the wake of the George Floyd murder.

The protest came here too. That summer, The Insider reported on a Black Lives Matter march in Boulder followed by another in Escalante. The paper even claimed the Escalante march was composed primarily of locals, which was in fact disputed by the locals.

That reporting proved to be one of the main catalysts that caused locals to seek for a fresh source of news — one that would honor local sentiment, rather than speak for it.

Youth Writing

In January of 2020, Escalante High School Principal Peter Baksis asked AJ Martel to substitute in English when the English teacher walked out. The teacher had been the second to walk out of English that year — leaving the students in a repeating merry-go-round of grammar.

It was evident the students had done no real writing that year, and the one journalism class had, since September, only put out two tabloid sheets of The Moqui Marble — their in-school publication.

“I only subbed a few classes but the state of those students left a lasting impression on me,” Martel said. “They had nothing to write for, and nothing to write about.”

Later in May, Martel told a neighbor (and former city council member) he had an idea. He said he wanted to act as a liaison between the school and The Insider to get student essays published.

But he had talked to neither the school, nor the paper about the idea. “You can’t work with the paper,” the neighbor said flatly. “You’ll have to start your own.”

The next week, Martel placed a call to Jerry Taylor. “I need a sanity check,” Martel said to preface the idea. Taylor then told him that a couple other people were already talking about starting a new newspaper, and put him in touch with Simone Griffin and Elaine Baldwin. “That call set the course for what has probably been the most insane project of my life.”

A Mission

In discussions between Martel, Griffin, Baldwin and a handful of other Garfield community members, a name for the project emerged — The Byway — with a nameplate designed by Tari Cottam.

A mission statement was also born, trying to explain the risky venture.

“While the world grows increasingly divisive, we are fed up with outside voices speaking on our behalf, yet misrepresenting our heritage, and the unique culture of one of Utah’s most remote regions,” read an editorial in The Byway’s first issue. “Therefore, this paper is this region’s forum dedicated to preserving our culture, and honoring our heritage.”

The paper would accomplish this in three ways. First, it aimed to be a forum for positive civil discourse. Second, it sought to unify Piute, Wayne, and Garfield counties with content written locally. Lastly, the paper would give the youth the opportunity to write and be read.

One Wild Ride

The editors of The Byway prepared for a September 11, 2020, launch date by writing articles and gathering content from other community members. Griffin and Martel (as youth coordinators) focused on coaching a group of Escalante students in writing essays to help explain the values of the paper.

“I want students to see that growing up in our communities teaches them life skills ‘city kids’ can’t get,” Griffin wrote in October, 2020. “We have hard-working, loyal teenagers who can do great things in life and can compete on any level.”

“The challenge was getting them to coherently put their ideas on the page,” Martel said. Members of the community would often ask Martel, “Did that kid really write that?” And he would respond, “Yeah, he really wrote that.” What people didn’t know was that it took a lot of time to coach these kids on how to write at all. “Their ideas were all theirs,” Martel said, “but they had trouble merely structuring an essay.”

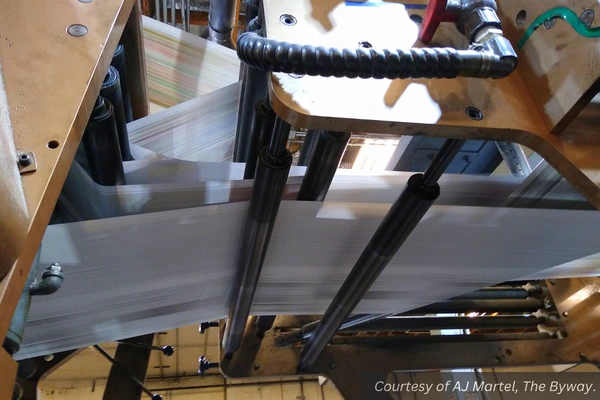

Printing a weekly newspaper was also a challenge. The printer was in Bullhead City, Arizona, and the bundles of paper would have to be sacked for shipping at the post office there.

No one at the postal service actually knew what cities the paper traveled to before arriving in Southern Utah. After the Escalante marquee announced the arrival of The Byway, the first issue didn’t actually arrive for nearly two weeks.

The staff quickly realized shipping would have to change. For a time, the printer had to box all of the paper to be shipped to Utah post offices, and then officially “enter” the mail again under the USPS Every Door Direct Mail program. It was expensive!

Later, the printer was able to start freighting the paper for entry at Richfield, which eliminated the boxes. Starting in early 2024, staff arranged with the printer to freight the paper for entry at Parowan, and then deliver it themselves to Garfield County towns and up Highway 89. Wayne’s papers would get dropped off in Monroe.

Designing a weekly, eight-page broadsheet paper was a new experience as well. No one had any training on Adobe InDesign, but they figured it out. Fortunately after only a few weeks of designing papers, student writer Nadia Griffin emerged as a talent in this regard. Only 15 years old at the time, she became the sole designer of nearly every issue of the paper until she left on her mission in the summer of 2024.

With this enormous effort each week, and the accompanying expense, the paper eventually went to a monthly publication supplemented by a website to reduce the financial losses and save the energy of the editors. Running a paper privately funded by local, middle-income volunteers might not have been a sustainable path, but they did the best they could.

The Local Effect

For the first few months of The Byway, writers focused mainly on positive stories and essays on specific topics. Political discussion, and even mentions of the pandemic were sparse. Though the paper at the time was milquetoast, some took issue with its presence at all.

“A new church newsletter is being circulated…” wrote Sheridan Wilder, who led an overwhelmingly negative campaign to get her partner, Byron Ellis, elected Garfield County commissioner.

It wasn’t until January 2021 that The Byway began publishing stories touching on more sensitive political and religious issues. After running a news story on the pardoning of Phil Lyman, a series on the Church’s Personal Development Youth Guidebook, a satire on tourists getting their Priuses stuck in the sand and an article about forest management, the paper started getting more significant pushback from the establishment.

Two writers from The Insider wrote terse emails, one of which cited The Byway’s “mean-spirited values.” The email continued, “The Phil Lyman apology piece, the stereotyping of California visitors as senseless prius-drivers, the generally-defensive posture, and the overtly religious content make this not a good fit for our household.”

Since then The Byway has received many letters, almost all from those on the left, protesting either the paper’s writing or its existence. Spotting opportunities for civil discourse, the editors frequently engaged with liberal commenters, urging them to write letters or full articles addressed to conservatives but without misrepresenting them. Very few responded to the invitation.

One time, a commenter dared us to print his fiery, anti-Trump letter to the editor. The editor said yes, but on one condition: “only if you allow me to print a rebuttal next to it,” the editor responded. “In the rebuttal, I won’t be defending Trump, but rather will address your straw man arguments.” In response, the commenter revised his letter into a very good anti-Trump piece and still was able to make all his points. It was excellent discourse.

On the friendly side of the ledger, the paper has received a handful of nice notes too.

Some readers have stated that they believed The Byway has actually tempered what was once solidly liberal discourse in the region. Some have even suggested that the sudden appearance of The Byway in the fall of 2020 actually caused Byron Ellis’s negative campaign to go quiet. In fact, shortly after, he put his house on the market and, within a week of losing the election, moved to Florida.

“I don’t know if I believe those claims,” Martel said. “Certainly there are lots of other factors at play that have caused local liberals to go quiet. But you never know. Maybe we did have some positive influence on the discourse.”

The Experiment

After a five-year experiment, has The Byway left any legacy? According to some, yes.

In a letter from Panguitch resident Harshad Desai comparing the Garfield County government to a cesspool, he incidentally offered one reflection on The Byway. “I thank BYWAY because it improved the quality of INSIDER,” he wrote. Uh, you’re welcome? It was very expensive!

Chagrin aside, The Byway aimed to provide content that better reflected its local readers. About 80% of the paper’s writers were conservative, matching its reader base. But gauging by the lack of local support for such a conservative read, The Byway has not lived up. Maybe it was the wrong medium to use in the digital age. Maybe the content wasn’t right.

Or maybe the mission wasn’t right. This was most clear in how the schools handled the youth aspect of The Byway mission. With a few notable exceptions (such as Piute’s Meri Vasquez, Wayne’s Lisa Stevens and Panguitch’s Natalie Perkins), school faculty were indifferent to the idea of their students writing for a community paper.

“I was eager to work with the students in polishing their pieces for publication, honing their skills of communication, and experiencing the thrill of seeing their names in print,” said editor Karen Munson. Munson had once been an English teacher. “But interest and support never materialized to the extent I had hoped.”

That was apparent in the most recent Christmas issue, which featured artwork and essays from elementary students. Wayne and Piute schools fully participated by submitting artwork to the paper. Yet, for the first time, the three major schools in Garfield County opted out — with one school citing privacy concerns.

Within the political realm, the paper’s platform for conservative voices also largely went unnoticed. In a February meeting with Garfield County officials in Antimony, one resident complained about the “liberal paper.”

“You know we also have a conservative paper, right?” Jerry Taylor asked the crowd.

“What’s that?” the person asked, and another answered, “The Byway.”

“Right,” Taylor said. “What have you done to support that paper?”

“Conservatives complain about how the media favors liberals,” Martel later said. “We could platform conservatives. We could even go to battle for them. But is that what they want? Will they support us?”

“All great experiments, like The Byway, are just that — experiments,” said Munson. “We may not get the results we expect, or even hope for, but we get feedback, and then we know the outcome.”

“Now we know,” Munson added. “We will never wonder ‘what if’ or feel the remorse of wishing we had tried but didn’t.”

At the prospect of losing The Byway, Baldwin lamented about surrendering the dialogue back to the liberals. She suspected that they would not give a platform to conservatives at all. “If The Byway goes away, what are we going to do?”

– The Byway

Feature image caption: The original junior staff writers of The Byway pose with the first 12 issues of the paper at Escalante High School, on December 10, 2020. The group of youth are flanked by coordinators Simone Griffin (left) and AJ Martel (right).