A recent poll showed many Utahns had significant concerns over drought, the Colorado River and an influx of new move-ins.

The poll, conducted yearly since 2011 by the State of the Rockies Project, was released last week for 2023 and was conducted the 5-22 of January. It surveyed attitudes from 3,413 telephone and online interviews in eight western states on conservation, public lands, outdoor recreation, energy policy and the Colorado River.

The results showed that, despite the rain and snow received this winter, Utahns still worry that it won’t be enough. And many see consequences not just in water-shortages, but also in Utah tourism and economics.

- 83% of people say the Colorado River is critical to the state’s economy.

- 86% view the river as an attraction for tourism and recreation.

- 76% of voters say the river is at risk.

- 78% say it is in need of urgent action.

Concerns over drought jumped up in 2022 and remain high this year. And over four-fifths, or 81%, of voters in Utah say that drought is an extremely or very serious problem, for a total of 95% agreeing that there is a problem. People from other states, on the other hand, were more likely to respond that the problem was serious, but not extremely so.

Among all the states, protecting sources of drinking water was seen as the most important conservation goal in Western States.

Additional concerns in Utah included water availability, overcrowding at recreation sites, and too many people moving to the state.

Background

It’s no surprise that Utahns are worried about the Colorado River. The poll comes at a time of increasing drought awareness in Western states. As reported in an article in The Byway’s last issue, the seven Colorado River basin states are in the middle of negotiations.

A 23-year-long drought has driven the Colorado River to its lowest water levels. Meanwhile downstream, Lake Powell is down to an elevation of 3,522 feet, a historic low since it was filled in the 1960s. At 3,490 feet Lake Powell stops producing hydropower; at 3,370 feet it cuts off water in parts of Arizona, Nevada and California altogether.

But in order to save the river, where will all of the water come from?

“There’s too little supply and too much demand,” water and climate scientist Brad Udall told the Washington Post. “Ultimately, I think what we’re going to see here is some major rewriting of Western water law.”

“And how this works out is anybody’s guess,” he said.

– The Byway

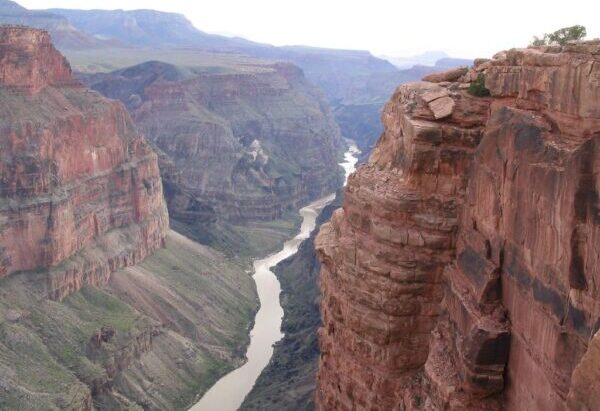

Feature image caption: The Colorado River going through the Grand Canyon in Arizona. Courtesy Flickr.