As first lieutenant of Tooele’s military company, Jacob Hamblin led a group of men into the canyon in another effort to hunt up the local Indians. At the break of dawn, Hamblin’s men had surrounded their camp.

For three years, since Tooele’s founding in 1851, the Natives had frequently stolen the settlers’ horses and cattle, causing the people to build their houses in the form of a fort for protection. For the new settlement, the thefts were more than a nuisance.

The chief sprang to his feet and said to Hamblin, “I never hurt you, and I do not want to.” The women in the camp fled, and the crying of the children aroused Hamblin’s sympathies. No one was injured that day.

The people in town seemed unimpressed with Jacob Hamblin’s lack of action. They urged him and the militia to try again. During the second round, the company surprised a band of Indians west of town in the Stansbury Mountains. One Indian approached Hamblin. Hamblin’s rifle misfired, and the Indian responded by shooting a series of arrows at Hamblin’s gun, through his hat, past his head, and through his vest. Hamblin threw rocks.

Surprisingly the other men in the company also experienced misfires that day.

Jacob Hamblin’s Impressions

Jacob Hamblin later reflected that he and the other men noticed a special providence had prevented them from shedding the blood of the Indians.

“The Holy Spirit forcibly impressed me that it was not my calling to shed the blood of the scattered remnant of Israel, but to be a messenger of peace to them,” Hamblin later recalled. “It was also made manifest to me that if I would not thirst for their blood, I should never fall by their hands.”

“The most of the men who went on this last expedition, also received an impression that it was wrong to kill these Indians,” he added.

History of Strife with Indigenous Peoples

The colonization of America has been a story of great progress and development, as the United States expanded its republic and proved to be the world’s great superpower. But this expansion was to the great detriment of Native Americans already living there.

In the nation’s early history, strife between Indigenous people and European settlers culminated in the 1830 Indian Removal Act. This Act, signed by President Andrew Jackson, ordered the removal of all Natives to territories west of the Mississippi River. The march of the Natives later became known as the Trail of Tears.

Early members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, led by their prophet Joseph Smith, had a unique perspective on their Indian neighbors. The Saints believed that the Native Americans were remnants of a lost tribe of the House of Israel, and the descendants of the Lamanites, a nation of people in The Book of Mormon.

Latter-day Saints maintained friendly relationships with Natives during their time in Illinois, with some Natives choosing to convert to the faith where they intermarried and received sacred temple ordinances. When the Saints were driven from Illinois, their encounters with many tribes along the trail to Utah were also peaceful, on account of the Saints’ positive attitude toward Indians.

Challenges after Coming to Utah

Moving in among the Natives of the Great Basin proved a challenge for the Saints, however. Jacob Hamblin had only arrived in Salt Lake City in 1850 after his conversion to the Church. After that he promptly moved to Tooele — a struggling new settlement in the heart of Goshute country.

Other parts of the Utah Territory saw struggles with the Natives — especially with the Paiute and Ute in Utah Valley, and southward in Sanpete and Sevier Valleys.

The cultural differences between the Natives and their new white neighbors could not have been greater. Not only did language barriers hamper effective communication and negotiating, but cultural norms also proved a challenge, especially when trying to resolve conflict.

Wakara’s War

Such conflict resulted in Wakara’s War in 1853, when a white settler, James Ivie in Springville tried to intervene in an argument between his wife and a local Ute. Ivie wounded several Indians, and one died. A military unit reported to Chief Wakara’s camp in Payson seeking a peaceful resolution. Although Ivie saw the incident as one of self defense, the Utes demanded retribution, seeking for the death of a Euro-American.

Intermittent fighting and violent acts continued for the following months, until Brigham Young negotiated a peace agreement with Wakara in Levan the following year. But after Wakara died in 1855, tensions re-emerged.

The Black Hawk War

In Sanpete and Sevier Valleys, white settlers continually encroached on lands critical to the Natives’ subsistence patterns, and Natives continued to steal livestock. In 1865 Black Hawk and a group of Utes met with a group of whites in Manti to settle disputes. This encounter ended poorly. During the remainder of that year, Black Hawk organized bands of Utes, Paiutes and Navajo and led them to steal more than 2,000 head of stock, killing around 25 of the white settlers.

The most intense period of the Black Hawk War was between 1865 and 1867, during which time an estimated 70 whites were killed. Many Indians were also killed. Unable to distinguish between friendly and hostile tribesmen, frustrated settlers at times indiscriminately killed Indians, including women and children.

Smaller Conflicts

In 1867 Black Hawk made peace with the settlers, but still some intermittent raiding and killing occurred until 1872. Federal troops had responded promptly to similar disputes with Natives in neighboring territories, but due to the antipathy of the U.S. government toward the LDS Church, requests for federal troops went unheeded for eight years. When 200 troops finally appeared in Utah in 1872, the war ended almost without incident.

The hardships the early Saints experienced living with neighbors who seemed to want to share in everything the settlers owned were no different than those of other settlers across the nation’s expanding territories. Constant thefts and threats of violence made pioneer life intolerable at times, and the Saints could have been tempted to use more force as others had in neighboring territories.

Jacob Hamblin’s Call to Assist the Indians

But the Church’s teachings on equality and policy on friendshipping the Natives remained unchanged. Shortly after Jacob Hamblin’s spiritual call to love the Natives, he received an official Church call.

In 1857 President Brigham Young made Jacob Hamblin the president of the Santa Clara Indian Mission. Young directed Hamblin to “continue the conciliatory policy towards the Indians which I have ever commended, and seek by works of righteousness to obtain their love and confidence. Omit promises where you are not sure you can fill them; and seek to unite the hearts of the brethren on that mission, and let all under your direction be united together in holy bonds of love and unity.”

Church headquarters frequently invoked assistance to the Indians when they called families to settle new valleys. Such was the case when residents of Monroe were called in 1873 “to settle in Grass Valley and assist the Indians.” Although the Black Hawk War had just ended, difficulties with the valley Natives were still common.

Later in 1873 when the non-Mormon McCarty brothers shot four Navajo who were passing through Grass Valley, Jacob Hamblin came to intercede and quell tensions between the Burrville settlers and the local Navajo.

Outsiders Noticed the Saints’ Respect Toward Indians and Each Other

In today’s post-Civil Rights era, it is difficult to fully understand the animosity between Native Americans and European Americans. But the Latter-day Saint approach to treating the Natives with kindness was unusual for its time, and outsiders took note.

On a trip from Salt Lake to Dixie in 1872, Brigham Young invited General Thomas L. Kane and his wife Elizabeth to join him. As a feminist, Elizabeth was a woman ahead of her time, but in regards to her views on Mormonism, she was like most outsiders who were fixated on the Mormons’ polygamous practices.

Elizabeth was leery about what she would see among the Saints in their new home on one of America’s wildest frontiers. Mostly, she expected to see oppressed women, but she found something else among the Saints, as she chronicled in her memoir, Twelve Mormon Homes (1874). One experience in Fillmore was especially striking to her.

Elizabeth’s own words: Twelve Mormon Homes

While Elizabeth’s hostess, Matilda King, was preparing dinner, five Paiute Indians came into the room and though uninvited, clearly expected to join the party. Elizabeth wrote that Matilda then addressed the Natives “in their dialect,” after which they sat down contentedly.

“What did your mother say to those men, Mr. Q [sic]?” Elizabeth asked the son curiously.

“She said, ‘these strangers came first, and I have only cooked enough for them; but your meal is on the fire cooking now, and I will call you as soon as it is ready.’”

“Will she really do that, or just give them scraps at the kitchen door?” Elizabeth asked.

“Our Pah-vants know how to behave,” the man answered. “Mother will serve them just as she does you, and give them a place at her table.”

“And so she did,” Elizabeth later wrote. “I saw her placing clean plates, knives, and forks for them, and waiting behind their chairs, while they ate with perfect propriety.”

– The Byway

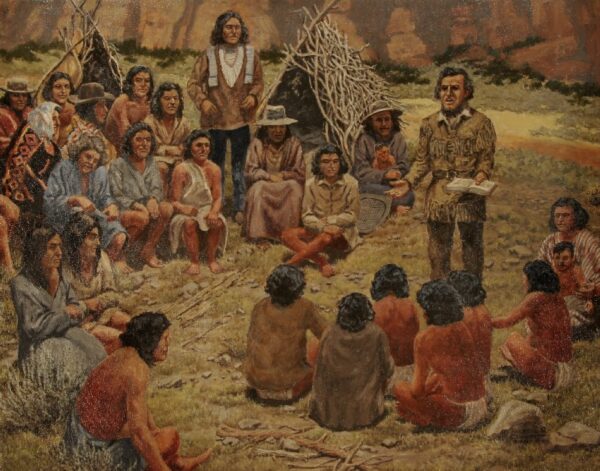

Feature image caption: Jacob Hamblin sharing farming practices with the Shivwits band of the Paiute near Santa Clara.

Quick Facts

Jacob Hamblin arrived in Salt Lake City in 1850 after his conversion to the Church.

President Brigham Young directed Jacob Hamblin to “continue the conciliatory policy towards the Indians which I have ever commended, and seek by works of righteousness to obtain their love and confidence.

Latter-day Saints maintained friendly relationships with Natives during their time in Illinois… When the Saints were driven from Illinois, their encounters with many different tribes along the trail to Utah were also peaceful, on account of the Saints’ positive attitude toward Indians.