In 1869, John Wesley Powell, the one-armed Civil War veteran, passionate geologist and natural historian, was feeling the itch to travel again.

As a young man throughout the 1850s, Powell had explored the rivers of the midwest. After fighting in the American Civil War between 1861 and 1867, he turned his attention in 1867 to exploring the West. He hiked several expeditions in the Rocky Mountains and around the Green and Colorado Rivers.

At the time Powell was exploring the West, Panguitch was barely settled and most of the surrounding communities did not even exist yet. It is said that he looked out over Utah territory from the highest point in Garfield County, now named Powell Point after him.

Then in 1869, Powell embarked on a journey down the treacherous Colorado River through the Grand Canyon to chart it. This was the expedition that would define his career.

Near the end of the journey, Powell wrote in his journal, “For years I have been contemplating this trip. To leave the exploration unfinished, to say that there is a part of the canyon which I cannot explore, having already nearly accomplished it, is more than I am willing to acknowledge and I determine to go on.”

Whether it was the trend-setter or the trend-follower, Powell’s exploration was part of a new age of fascination with remnants of the untamed Native American West. It jump-started an interest particularly in the “antiquities,” such as buildings or pottery left behind by Native Americans. This set the stage for an extremely powerful piece of legislation called the Antiquities Act.

History of the Antiquities Act

Ten years after Powell’s trip, by 1879, citizens and scholars had increasingly taken interest in the archeological sites in the West. Powell, who had returned from the expedition with a fascination with the natives, had been appointed director of the federal government’s newly formed Bureau of Ethnology, dedicated to spreading knowledge of the American Indian.

Soon, non-experts began digging and collecting archaeological artifacts from historical sites. A coalition of scientists and politicians, Powell included, seeing an immediate need for preservation of these sites, urged passage of a protection act. After Powell’s death, the legislation passed.

The Antiquities Act, signed into law by Theodore Roosevelt in 1906, was the first law allowing the federal government to protect cultural and natural resources in the United States.

The text of the act itself is quite simple. Here are the first paragraphs:

The President may, in the President’s discretion, declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated on land owned or controlled by the Federal Government to be national monuments.

The President may reserve parcels of land as a part of the national monuments. The limits of the parcels shall be confined to the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of the objects to be protected.

In 1950, after the creation of Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming gained an exemption from any future monuments being created without congressional approval. Since 1980, Alaska has had a similar exemption for monuments over 5,000 acres.

Could Utah get such an exemption? Unlikely. But the state could prompt a reform of the Antiquities Act.

There has been quite some debate over limiting monuments to the “smallest area compatible,” as well as over what objects the act is actually meant to protect.

The Congressional Research Service writes in “National Monuments and the Antiquities Act,” a resource for members of Congress, “Some critics charge that, because the original purpose of the act was to protect specific objects, particularly objects of antiquity such as cliff dwellings, pueblos, and other archeological ruins (hence the name ‘Antiquities Act’), Presidents have used the act for excessively broad purposes.”

The document continues, “Supporters of current presidential authority counter that the act does not limit the President to protecting ancient relics, and maintain that ‘other objects of historic or scientific interest’ broadly grants considerable discretion to the President.”

Chief Justice Roberts, in a case involving the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument, wrote that “the Antiquities Act originated as a response to widespread defacement of Pueblo ruins in the American Southwest.”

“And while we have suggested that an ‘ecosystem’ and ‘submerged lands’ can, under some circumstances, be protected under the Act,” he wrote, “we have not explained how the Act’s corresponding ‘smallest area compatible’ limitation interacts with the protection of such an imprecisely demarcated concept as an ecosystem.”

The petition that Massachusetts lobsterman had brought for certiorari was denied, but the Chief Justice’s statement did question the broad authority given to the president under the Antiquities Act.

How Many Times the Antiquities Act Has Been Used

How the Antiquities Act should be used is discussed extensively elsewhere. And there are many different legal interpretations of such a simple text whose intent has been broadly debated.

What this article shows is that the act is used quite differently today than when it was first created. Once used to protect archaeological artifacts, the act is now used to protect entire ecosystems. And such protections have become partisan.

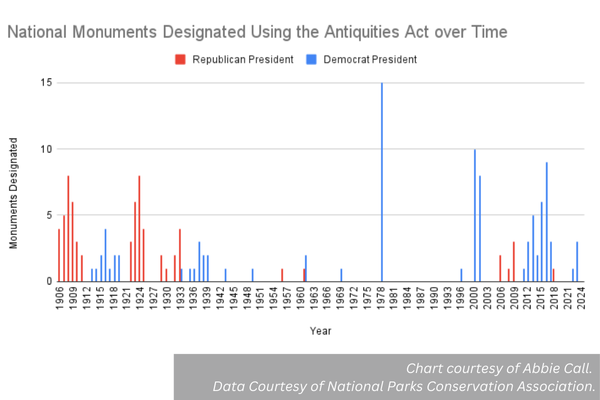

The Antiquities Act has been used by 18 United States presidents to designate 161 national monuments. For a long time, President Theodore Roosevelt, a Republican president, held the record for the most national monuments at 18, which he designated between 1906 and 1909.

For 50 years between the 1940s and 2000, not many national monuments were designated, with the exception of Jimmy Carter’s controversial 15 in Alaska. By the 2000s, the designation of national monuments using the Antiquities Act had become more partisan, with Democrat presidents declaring the majority of monuments. President Bill Clinton, a Democrat president, broke Teddy Roosevelt’s record in 2000 with 19 designations.

The Antiquities Act Today

Today, many conservatives, especially Western conservatives, argue that the Antiquities Act is overused and abused. On July 24, the Congressional Western Caucus invited a panel to Washington, DC, to discuss the abuses of the Antiquities Act and its impact on local landowners.

At the meeting, representatives and panelists acknowledged many national monuments that were done right, listing places like Dinosaur National Monument on the Utah-Colorado border, and Cedar Breaks between Hatch and Cedar City. Bryce Canyon was also once a monument created by the Antiquities Act in 1923.

What is now Dinosaur National Monument was one of the areas Powell spent a lot of time exploring on his famous expeditions. He enjoyed how the “waters waltz their way through the canyon, making their own rippling, rushing, roaring music.” That was before dinosaur bones were discovered there, yet today it serves as a beautiful recreational tourist destination as well as a national monument.

Other monuments throughout history, though, were too large, had unclear goals, and clashed with local economy and culture. The Grand Staircase and Bears Ears national monuments in Utah are a few good examples. Many contemporary monuments are created in order to combat natural resource development. This is the worry with rumored monuments in Oregon and southern New Mexico.

“People are claiming widespread local support of the Mimbres National Monument for ‘protecting the mountains,’” New Mexico Representative Jennifer Jones told the Western Caucus Board of the proposed Mimbres Peak National Monument in southern New Mexico.

The monument would cover 245,000 acres of mountain land, and the campaigns say it will protect the mountains and bring tourism. “We know this won’t work,” said Jennifer. The real reason for the monument, she said, would be to stop magnesium mining, a purpose she and most of her constituents did not support.

The Lie of Using National Monuments for Tourism

Proponents of Western national monuments like the Mimbres adore the Antiquities Act. The National Parks Conservation Association calls the Antiquities Act “one of our nation’s most important conservation tools.”

Other arguments are interwoven with recreational and economic opportunity. “Since 1950, 17 national monuments have been created in the Mountain time zone alone,” Adam Larson, a contributor to Writers on the Range, wrote in 2022, “protecting archaeological sites, fossils, historic landmarks and recreational opportunities, while also attracting millions of visitors (and their wallets).”

But locals who have lived through the creation of unreasonable national monuments tell a different story. “To say the Grand Staircase [National Monument] is tourism is complete propaganda,” Leland Pollock, a commissioner from Garfield County, told the Western Caucus Board, listing ways the monument has hampered Garfield’s economy rather than helping it.

One of Leland’s biggest frustrations was that managers of the monument did not seem to understand the Antiquities Act themselves. When he had talked to the monument managers about promoting more tourism, one of them had been offended. “It was not created for tourism,” she said. “That’s against the original intent of the proclamation.” But the Antiquities Act states nothing about blocking tourism in national monuments.

Nonetheless, the preferred alternative for resource management on the Grand Staircase was in line with this manager’s view. It included low maintenance or closure of roads, outlawed ATVs and target shooting, and general efforts to keep visitors and Garfield County officials off the monument. The revised alternative, while still not encouraging much tourism, has slightly relaxed these restrictions.

Representative Celeste Maloy added that the Antiquities Act has become “a way of scoring cheap political points without a lot of political process or input. And the outcome matters, but so does the process.”

Representative Mariannette Miller-Meeks from Iowa is currently sponsoring a bill in the House that would require presidents to get congressional approval before using the Antiquities Act. It was introduced in September of 2023, and it is currently making its way through subcommittees. The bill has 18 cosponsors, two from Utah.

Honoring the Act’s Original Purposes

John Wesley Powell described the Grand Canyon as “scenery on grand scale. Marble walls polished by the waves.” He was truly awed by the “vermillion cliffs,” marble amphitheaters, and life-giving rivers of Colorado, Utah and Arizona.

In Powell’s time, the American West was still a big, new, unexplored frontier, even considering the influence of budding Latter-day Saint settlements across both northern and southern Utah. Powell and many others, with their fascination for the places and peoples of the Grand Canyon, the Green River and Echo Park, had good reasons to want to protect antiquities of the West. But their scope may not have been so broad as to include a lot of what the Antiquities Act is used for today.

There is danger in broadening this definition to include unimagined scientific developments, partisan policies, and technologies of today. It is the task of politicians, monument managers, and citizens to be cautious of modern meanings we might try to overlay on the original missions of the Antiquities Act.

– by Abbie Call

Feature image caption: Steamboat rock, which some stories say John Wesley Powell almost died climbing to take scientific measurements. He was saved by his companion, George Y. Bradley, who pulled Powell up using Bradley’s pants. Courtesy of NPS/M. Reed.

Abbie Call – Cannonville/Kirksville, Missouri

Abbie Call is a journalist and editor at The Byway. She graduated in 2022 with a bachelor’s degree in editing and publishing from Brigham Young University. Her favorite topics to write about include anything local, Utah’s megadrought, and mental health and meaning in life. In her free time, she enjoys reading, hanging out with family, quilting and hiking.

Find Abbie on Threads @abbieb.call or contact her at abbiecall27@gmail.com.