“Three Branches, One Government” is the first of four articles focused on defending the U.S. Constitution. These articles, written by The Byway‘s four editors, were published in the newspaper’s most recent September paper.

Our Founding Fathers lived much of their lives in fear and trepidation, that we might live in peace. They not only fought a war for our independence but they put their lives on the line for many years, so that we may live in peace today. They declared their independence, fought for it, and then had to set up a new government like the world had never seen before. It was a lifelong pursuit. All because of the desire for freedom.

The Founding Fathers needed to set up a government that could stand the test of time. They were creating a God-inspired government that could protect this new infant country and keep it safe for as long as the people would live righteously.

These men not only put their lives and their sacred honor on the line but they also put the lives of their families and friends and every man in America in jeopardy if they should fail to create a government that could last.

They read John Locke, Sir William Blackstone, Roman law; they studied and pondered on what type of government would work better than the Articles of Confederation, which was failing to meet the needs of their new country. They knew they did not want a king, as they had just spent the last eight years fighting and many years before that, determining that form of government would not give them the freedom that Americans desired. Freedom was what America was all about.

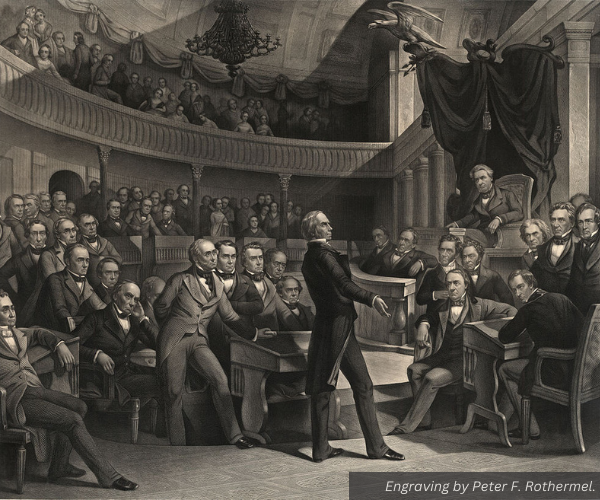

In the summer of 1787, state delegates met to draft a new Constitution. During the day they would meet and discuss, and even change long-held ideas. During the evening they would go to the pub and discuss some more and maybe change some minds again. It wasn’t an easy process and it seems that everyone had to give up something they held dear to create a government that could stand the test of time.

From the years 1774 to 1789, 435 different delegates served in the Continental Congress — usually 35 to 57 at a time. Although not all of these delegates participated in the writing of the Constitution, their combined experience led to the ultimate result of the Constitution.

The government they finally settled on was like no other government that had ever existed on the earth before. They wanted a republic instead of an all-powerful king, or a king and a parliament, or senate as the Romans had.

They settled on three branches of government. Each branch was to be equal in power and authority. Each branch was to control the other so that no branch could run roughshod over the other two. Those controls were written into the Constitution of the United States of America. Our Constitution has worked to keep us free for the last 235 years and hopefully will stand another 200 years.

At different times one branch of the government has exerted its authority and seemed to rule for a time until checked by one of the other branches when they have gotten out of hand. This was as the Founders envisioned it would happen.

Each branch of government kept the others in check so that no branch became so powerful that they controlled the country. Many times the personalities of individuals or circumstances in history determined which branch would take the lead in the direction our country went.

The Legislative Branch

The authors of the Federalist Papers asserted that the legislative branch was the most powerful branch of government.

This was not just a casual observation. An important reason they were interested in so arguing was their concern that the Legislature might overwhelm the power of the rest of the government, and attempt to rule on its own.

This view was stated most directly in Federalist 48 in which James Madison, writing of the governments of the individual states, observed that “the legislative department is everywhere extending the sphere of its activity and drawing all power into its impetuous vortex.”

This is one of the main reasons the Framers created two houses of Congress — that the power may be dispersed equally between the Representatives and the Senators. This branch of government was thought to be the closest to the people and the Framers felt they would understand the will of the people. Today many people see them as an entity of their own that fails to listen to the people.

The writers of the Federalist Papers, under the collective pseudonym Publius, endorsed the plan to create two houses of Congress, and to give them non-overlapping duties and make them work together on other duties. These can be thought of as dispersing the power of Congress making the legislative branch less cohesive in its action.

If the two houses of Congress can work together much can be accomplished, but if they are at odds, as they frequently are currently, they become an ineffective branch of our government. Only when Congress can bury their differences and work together can they move forward and accomplish what needs to be done to run the country effectively.

Framers granted the authority to make laws to the Congress, which the Framers felt would make it the most powerful branch of the government. In order for this to happen they need to be able to work with each other to pass wise laws. Congress has always struggled with being able to make laws that work for a nation as large as America, and it was this way even when there were only 13 states. Imagine the time it takes today.

Executive Branch

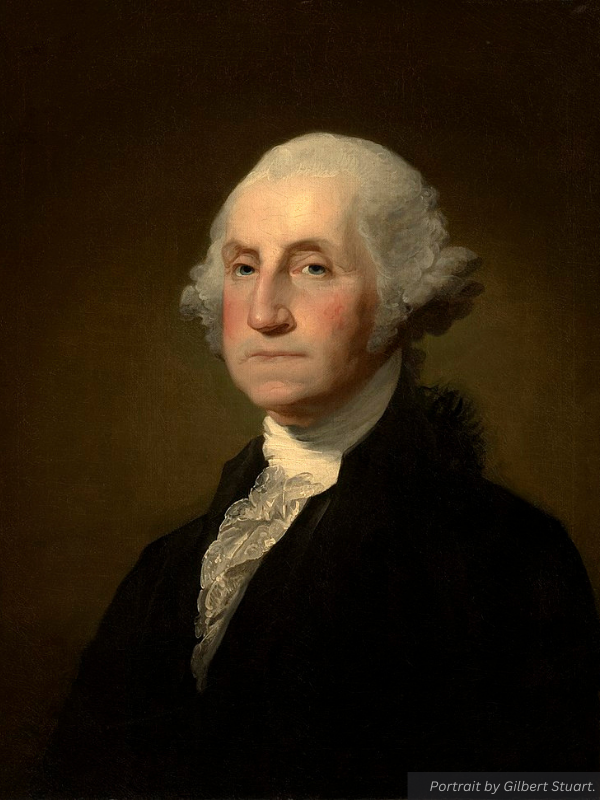

Throughout history the executive branch of our government has led the way in determining which direction our country would go. An example of this is when George Washington stepped down after two terms in office. He could have easily stayed and become a king if he wanted, as the Constitution did not state how many terms of office a president could serve.

It was not until Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected for his fourth term that Congress became worried and added the Twenty-Second Amendment, which stated that a president could serve for only two terms.

Notably Congress was concerned if he had served for a full fourth term it would not be in the best interest of the country and corrected what could have been a grave error for future generations of our country.

Today the executive branch is arguably the strongest branch of our government by virtue of the size of the administrative state, its rule making authority and its power to interpret rules prior to the overturning of Chevron Deference just a couple months ago.

With all the federal agencies housed under the executive branch, that branch employs a workforce of nearly 1.2 million people (other than Department of Defense) at the current time. This massive government can’t help but touch everyone’s life in America.

That fact alone changes how we might think of something Thomas Jefferson said in 1824. “I think that we have more machinery in government than is necessary;” he said, “too many parasites living on the labor of the industrious.” One wonders what he would think today.

Judicial Branch

At the time the Supreme Court was created by the Framers of the Constitution there had never been such an institution in the Americas. Under the Articles of Confederation, the state courts had been expected to resolve legal disputes. Almost all decisions were decided at the state level but the need for a more powerful central government and the need for a sense of finality and uniformity to American law led to the establishment of a federal judiciary. Justices would serve for life “during good behavior.”

The first Chief Justice, John Jay, soon realized the case load was not nearly that of the state courts. The Supreme Court exercised little power and for the first few years after the Constitution was written, they were largely ignored in favor of state courts.

That changed when John Marshall was appointed Chief Justice of the court for the next 34 years. Marshall, who had served with Washington at Valley Forge, led the court strictly relying on the Constitution as he interpreted it.

Even though the Congress approved the justices’ appointments, little was done to change the makeup of the court. Several major decisions made by the Marshall Court such as Marbury v. Madison reminded the nation of the power of the Supreme Court even overruling a decision made by Congress.

Landmark decisions, such as the Dred Scott decision in 1857, showed that the Supreme Court was to be reckoned with and could not be ignored as Congress and the lower courts sometimes tried to do.

Although the executive branch seems to have dominated the running of America with its many agencies, the Supreme Court has challenged its power recently. Their decision in Loper Bright Enterprises this year, which overturned the 40-year-old Chevron Deference doctrine (discussed recently in The Byway in an article by AJ Martel) made heads spin in government agencies and put the executive branch on notice that they didn’t have authority on everything.

The Loper decision could change the way these agencies run their offices and establish rules. Other pending lawsuits such as the several by the State of Utah regarding federal lands may continue to curtail agencies’ power over our lives and our lands.

An Ineffective Government

When we have a strong, wise leader in our government that is willing to work with Congress, much can be accomplished.

At the current time these three branches of government spend so much time arguing with one another and trying to undo each other’s work that little is accomplished. A simple discussion in Congress turns into weeks of hearings and committee meetings that leaves meaningful legislation forgotten and neglected.

History can help us solve this quagmire if we will but learn from it. When the Founders of our country ran into this problem some cooler heads had to step in and take some action.

As the story goes, and as told by Karen Munson in her article, Benjamin Franklin suggested the delegates at the Constitutional Convention have a prayer. May we likewise pray as we continue to build up our nation today.

Powers in Practice

For the majority of the time three branches of government have been able to keep our country from swinging too far to the right or to the left. The separation of powers outlined in the Constitution act as checks and balances to each other’s unreasonable wishes.

As an example, one of the most important responsibilities given to Congress by the Framers as a check on the executive branch, was the power to declare war. America cannot go to war without Congress declaring war. Congress has been at its strongest when they have unitedly declared war and funded it adequately.

However, the executive branch has sent many of our soldiers to fight undeclared wars by sidestepping the “declare war” clause. This has cost America billions of dollars and many American lives. Only the Congress has the power to stop this by challenging the executive or defunding such actions, but they rarely do.

On the legislative front, the Founders felt that laws should be easily understood by the people so they could be easily obeyed. In Federalist 62, James Madson wrote “It will be of little avail to the people that the laws are made by men of their own choice if the laws be so Voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood.”

Joseph Postell of the Heritage Foundation wrote, “Where we go from here will depend on how well we understand and implement the lessons of History, which makes the examination of Congress’s evolution indispensable.”

As the Founding Fathers did, may we study, learn, and use the lessons of history to build our country and secure freedom for future generations.

– by Elaine Baldwin

Read more from Elaine in Where Is America Going?

Elaine Baldwin – Panguitch

Elaine Baldwin is an Editor/Writer for The Byway. She is the wife of Dale Baldwin, and they have three children, 11 grandchildren and one great granddaughter. Elaine enjoys making a difference in her world. She recently retired after teaching Drama for 20 years at Panguitch High School. She loves volunteering and finds her greatest joy serving in the Cedar City Temple each Friday.