No, the Utah Pioneers are not the colonizers you hear about in today’s racial politics.

Colonization has been an important story in world history, as nations, cultures and peoples rise and fall. Some of those lost cultures appear to merge with other groups or die off from natural causes — as is suspected with the ancient Anasazi of this region. But it seems that most cultures are destroyed violently … by other cultures.

It’s a cruel world. In America now, most of us have so far been spared from that cruelty.

Peacetime in much of the developed world has brought us to a new sensitivity to injustice and a heightened sense of our own morality. The new morality has led many in our country to condemn the acts of other cultures still engaged in conflict, and also to condemn our own forefathers for how they dealt with conflict.

Some have even denounced the very principles on which this nation was founded, which they view as the trespass of slave owners occupying land they stole from Native Americans.

Today in Utah we have to come to grips with yesterday’s values, as seen through the lens of today’s values. These are colored with the hues of racial politics and social injustice.

In America’s westward expansion through the 19th century, one group of Americans has stood out like a sore thumb. Though many groups moved to occupy the West — such as the Oregon Trail pioneers, the gold rush Forty-niners and the Okies of the Dust Bowl exodus — the Mormon pioneers have most frequently been criticized for their displacement of local Native Americans.

Much of this criticism has been at the behest of environmental activists the last three or four decades in arguments over public lands. But this trend has been exacerbated in the recent few years as environmentalism has married with the newly-heated topic of racial justice, to spawn a new movement called environmental justice.

During this time many activists have called for reparations for oppressed minority groups. These calls have almost exclusively focused on benefiting marginalized Black communities and descendants of slaves. Very rarely are Native Americans mentioned in the reparations discussion. Reparations for white colonization and displacement of Native Americans is only invoked, it seems, in the public lands debate, and especially in Utah.

The idea of offering reparations for early colonization, though, is fraught with problems. In an article published by the Library of Economics and Liberty, Bryan Caplan lays out an argument about why returning “stolen property” 150 years later doesn’t really work in Western legal doctrine. He concluded that the argument claiming lands should be returned to Natives “is just the doctrine of collective guilt masquerading as a defense of property rights.”

Commenting underneath Caplan’s article, Mike Rulle pointed out that if we were to seek the true owners of any piece of property under the reparations argument, we would not actually find who originally owned it. He wrote:

Not all people who lose power struggles are worthy of return. First, we would have to trace who took what from whom among the American Indians. We might also have to trace back to when we believe the American Indians became American. I think it is believed they came from East Asia across Alaska—at least some part of the population. Then we would need to figure out who may have screwed who in Asia and get that settled out.

Unless we have a timetable of how far to go back. Maybe limit it to 200 years. But then Europe would really have a mess to untangle. So many empires, so many unwound. Then Russia and East Europe. Germany and the Jews. China and the intellectuals. The Africans who participated in the slave trade would share costs with their English and American trading partners among current black Americans.

Why are we even theorizing on such topics? Mankind can be brutal. I assume this is not new information. We exist today with current laws. It is hard enough to do that right, let alone try to correct a billion wrongs.

This is an infinite regress.

When looking back on American history and seeing how European immigrants treated Native Americans, I understand why so many today are upset. Perhaps one of the great crimes of this nation was the 1830 Indian Removal Act, which forcibly removed Natives in the Eastern United States to the Oklahoma Territory.

In a similar way, I understand why some may be offended at the treatment of Natives at the hands of Utah’s own settlers, especially with the grim narratives written by the environmentalists, the anti-Mormons and the Salt Lake Tribune. But a look at Utah history reveals a much more nuanced story about the early Latter-day Saints and the Natives.

The mere presence of conflict does not imply wrongdoing. In spite of the vast cultural differences between the two groups and their difficulty in communicating, both the Natives and early Church leaders believed they could coexist.

Settlers and Natives successfully worked through many disputes for the three decades following the Saints’ first arrival. Later the federal government removed the Natives to reservations, which later got smaller and smaller.

It is impossible to know if the Latter-day Saints would actually have found harmony with the Natives had the federal government not removed them. But I believe that they would have. I believe this for four reasons:

- The Saints taught love for the Natives, sought diplomatic responses to conflict and respected others’ freedom to choose.

- In efforts to mutually assimilate, Church leadership sought guidance from Natives, and in return taught many of them to farm.

- Because the Saints had also been forcibly removed from New York, Ohio, Missouri and Illinois, they could be more careful not to infringe on other peoples.

- Clashing cultures, with enough time maintaining a civil discourse, can become more familiar with each other, and find ways to work together.

I would caution people not to criticize early Church leaders or blame them for “colonizing” Indian territory. I also urge people to not criticize today’s Church for what they perceive as wrongs committed by another generation.

I believe that had the Saints been granted more time with the Natives before federal removal, they could have found harmony. Such harmony is not the crime of colonization that so many speak of. And certainly a Latter-day Saint solution would have been vastly better than the federal solution of the time, which resulted in the horrific decimation of the great nations of Indigenous America.

– by B.E. Davis

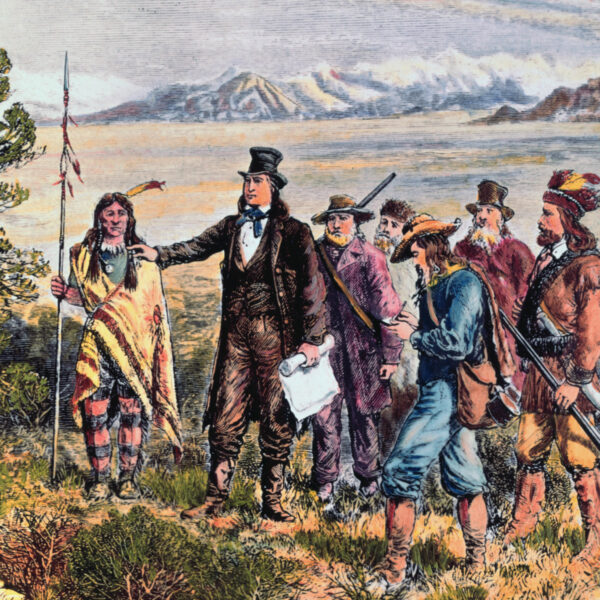

Feature image caption: Brigham Young overlooks the Great Salt Lake shortly after arriving in the Salt Lake Valley. Courtesy Getty/History.com.