How woke principles and the culture wars have distracted progressive organizations from achieving their missions.

The political fervor of 2020 was unforgettable. As a pandemic had rendered an entire population homebound and nervous, progressive organizations saw a chance to burn Donald Trump out of the swamp for good.

Meanwhile, protesters and rioters, overcome with a new racial reckoning, threw bricks through windows, burned out small businesses on Main Street and tore down statues of historical figures that didn’t stack up to the new morality.

With the mob in control, organizations and politicians everywhere were forced to pick sides — either to march with the mob, or get canceled. “We need to stand up and say that Black lives matter,” Utah Senator Mitt Romney said as he marched with protesters toward the White House in June, 2020.

Black Lives Matter march in Washington D.C., June, 2020. Courtesy Mitt Rom-

ney/Twitter.

The tide of progressivism was also felt in rural America and even locally. Just a week after Romney’s march, dozens of protesters drove from over the mountain to hold a march in Escalante — posing for the camera as they made their way up Main Street.

The following November, the movement proved successful. Joe Biden was elected as President, and both the Senate and House were taken by Democrats in a perfect trifecta of power.

As President Biden sat down for the first time in the Oval Office, progressives, unions and environmental activists had lined up a raft of executive orders for his signature. It was a time of great jubilation for these warriors: finally, after four years of tyranny, they finally had the power to execute life-changing policy for a better world.

But within a few months, the tide seemed to have changed. At first, it appeared to be President Biden’s waning popularity, especially after the botched withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan.

Even locally, it was eerily quiet. “Where is the Rural Utah Project?” I asked. “Where is the liberal watchdog, Garfield County Taxpayer Alliance?” To which an unsurprised Garfield County Commissioner Leland Pollock responded, “If I were a Democrat, I’d be hiding under a rock right now,” referring to the growing embarrassment over President Biden’s leadership.

Last month, progressive journalist Ryan Grim noticed something brewing in the liberals’ left wing: internal meltdowns have brought progressive advocacy groups to a standstill. Grim wrote a 10,000-word piece in The Intercept after investigating what was going on — and while Grim and I disagree on ideology, I have come to respect his honest analysis. His piece, “Elephant in the Zoom,” is worth the read and a great lesson for anyone involved in a nonprofit organization.

The stories coming from troubled progressive groups serve as a warning that employees and volunteers in any organization can exploit identity politics for personal gain. Groups can lose sight of their core mission, and staff can make a workplace environment toxic through callout culture.

Asleep During Roe v. Wade

In June 2020, organizations huddled with staff to see how they could respond to the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police. At Guttmacher Institute, the premier research organization for the abortion rights movement, VP of Public Policy Heather Boonstra asked her staff if there was anything Guttmacher, as an organization, could do to counter social injustice.

The Guttmacher staff’s answer surprised Boonstra. Turning inward, the staff was more interested in “loosening deadlines and implementing more proactive and explicit policies for leave without penalty.” They also suggested racial equity training, and doing something tangible for Black employees.

Boonstra noticed that her understanding of Floyd’s killing was totally different than that of her staff. She was focused on the work of the nonprofit, but the staff used the moment to focus on themselves.

Grim wrote that the Guttmacher staff had used “a moment of public awakening to smuggle through standard grievances cloaked in the language of social justice. Often, as was the case at Guttmacher, they played into the very dynamics they were fighting against, directing their complaints at leaders of color. Guttmacher was run at the time, and still is today, by an Afro Latina woman, Dr. Herminia Palacio.”

The problem of staff directing their complaints at leaders of color is not just a Guttmacher problem. “The most zealous ones at my organization when it comes to race are white,” said one Black executive director at a different organization.

That one huddle at Guttmacher led to months of infighting at the organization as staff used racial and political identity to shield themselves from performance reviews, taking energy away from Guttmacher’s mission.

In recent months, turmoil at Guttmacher, as well as Groundswell Fund, one of the largest funders of reproductive justice organizations, has been focused on unionizing staff as an attempt to address perceived injustices at work. Groundswell was successful after spending five months on the effort. Guttmacher was not so lucky.

On May 2, employees of Guttmacher finally posted publicly that they had been attempting to unionize for months and had just sent a letter to management seeking recognition. That very night, Politico rocked the abortion rights world by breaking the news the Supreme Court planned to overturn Roe v. Wade. It was the moment abortion-rights orgs had been preparing themselves for, but Guttmacher was caught sleeping on the job.

efforts to form a union, right during the heat of Roe v. Wade.

Courtesy of OPEIU/Twitter.

The next day, Guttmacher staff, in a moment of tone-deafness, posted a follow-up to their unionization efforts on Twitter — and moments later, after reading responses to their tweet, added they “were still reeling from last night’s leaked draft of the #SCOTUS decision to overturn Roe.”

Loretta Ross, another reproductive justice activist, was critical of Guttmacher staff as totally blind on the very day they were called to arms. “It’s a symptom of poor threat assessment,” said Ross. “They can’t identify the main threat.”

Elephant in the Room

Grim spoke with executive directors at a number of progressive nonprofits, many of which asked to speak on internal strife anonymously for fear of backlash from their own staff and donors. As he found, the dysfunction of these progressive organizations has become so widespread that stories of turmoil have increasingly leaked into public view.

“To be honest with you, this is the biggest problem on the left over the last six years,” one executive director concluded. “This is so big. And it’s like abuse in the family—it’s the elephant in the room that no one wants to talk about. And you have to be super sensitive about who the messengers are.”

“To be honest with you, this is the biggest problem on the left over the last six years.”

Grim pointed out that Democratic control in 2021 came with broadcasting a bold vision of “transformational change”, starting with the $1.9T American Rescue Plan and later with Build Back Better, which promised to pour billions of dollars into funding progressive wish lists.

“And then, sometime in the summer, the forward momentum stalled, and many of the progressive gains lapsed or were reversed,” Grim wrote. “Instead of fueling a groundswell of public support to reinvigorate the party’s ambitious agenda, most of the foundation-backed organizations that make up the backbone of the party’s ideological infrastructure were still spending their time locked in virtual retreats, Slack wars, and healing sessions, grappling with tensions over hierarchy, patriarchy, race, gender, and power.”

One former organization leader wrote that so much energy had been devoted to dealing with “internal strife and internal bullshit that it’s had a real impact on the ability of groups to deliver.” He estimated that during his last nine months, he had spent 90 to 95 percent of his time on internal strife, adding that the amount was similar for his deputies as well.

One senior progressive congressional staffer said that even outside the dysfunctional groups, the discord is still noticeable. “I’ve noticed a real erosion of the number of groups who are effective at leveraging progressive power in Congress,” said the staffer. “What they’re lobbying on isn’t relevant to the actual fights in Congress.”

One senior leader at an organization talked about the difficulty in actually addressing workplace problems. He stated that staff had a serious problem with “cancel culture” and “callout culture”. But since those terms had been coined by the right wing, they couldn’t even address the problem because they refused to adopt that language and framing.

“I got to a point like three years ago where I had a crisis of faith, like, I don’t even know, most of these spaces on the left are just not—they’re not healthy,” he said. “The toxic dynamic of whatever you want to call it—callout culture, cancel culture, whatever—is creating this really intense thing, and no one is able to acknowledge it, no one’s able to talk about it, no one’s able to say how bad it is.”

The Problem with Callout Culture

“Callout Culture”, which focuses on identifying injustices publicly, has essentially replaced much-aligned bullying, and has become the weapon of choice for the woke. While organizations deal with their internal reckoning on sexual, racial and gender identity, callout culture is the mechanism that weaponizes these culture war debates.

If it were constructive, callout culture could be the means of pointing out mistakes for the purpose of fixing them — and healthy discourse over disagreements is important to any organization with a unified mission. But the negative version of this, which was once quarantined inside the most radical organizations, has now leaked into mainstream progressivism.

“We used to call it ‘trashing,’” said Ross, referring to her activism work in the 1970’s.

Jo Freeman defined “trashing” in a 1976 article in terms which seem familiar today: “Trashing is a particularly vicious form of character assassination which amounts to psychological rape. It is manipulative, dishonest, and excessive. It is occasionally disguised by the rhetoric of honest conflict, or covered up by denying that any disapproval exists at all. But it is not done to expose disagreements or resolve differences. It is done to disparage and destroy.”

Ross argues that callout culture, if its goal is to root out and correct mistakes, thwarts its own goal because callout culture is fixated not on redemption, but punishment. The punishment of shame and cancelation has become the new firing squad. “If someone has made a mistake, and they know they’re going to face a firing squad for having made that mistake, they’re not gonna wanna come to you and be accountable to you. And so the whole callout culture contradicts itself because it thwarts its own goal.”

Ryan Grim noted that the problems plaguing progressive groups are not only evident in nonprofits, but also in politics, campaigns, and for-profit companies.

The Washington Post, which has been respected for its journalism standards for most of its history, has recently been embroiled in staff infighting over Dave Weigel’s retweet of a sexist joke. A colleague didn’t think it was very funny, and has taken to the public form (Twitter) to disparage Weigel — and other of her opponents, rather than resolving the issue privately.

But in a new turn, some companies are taking a stand against the mob of bullies. Netflix, deciding not to go Disney’s path, stood up to its wokest employees by telling them that the company would not censor content and instead would allow viewers to decide what they wanted to stream. Then, Netflix announced they would layoff employees who continued to protest the company’s decision.

Kraken, the crypto startup, took a similar stance in June inviting their wokest employees to leave — noting that staff was spending too much time focused on culture issues than fulfilling the company’s purpose.

Justice Over Environment

Internal turmoil has also been a problem in the environmental movement, notably in the National Audubon Society and The Sierra Club, which both were sidelined on their main environmental mission to deal with racial reckonings.

The expectation of protestors in 2020 was that all progressive organizations, if they were truly progressive, would depart from their main missions to address the race question. Local orgs were not exempt: Rural Utah Project, a sister of the environmental activist Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, had previously been successful in leveraging the Navajo Nation in bolstering the Democratic vote, and in advocating for national monument protection of Bears Ears.

But in the summer of 2020, they turned their attention to the national topic of racial injustice, posting on their Facebook page a scathing rebuke of Utah for having one of the highest rates of police shooting Blacks, per capita. It was hardly a Rural Utah issue, but an issue RUP could not resist nonetheless.

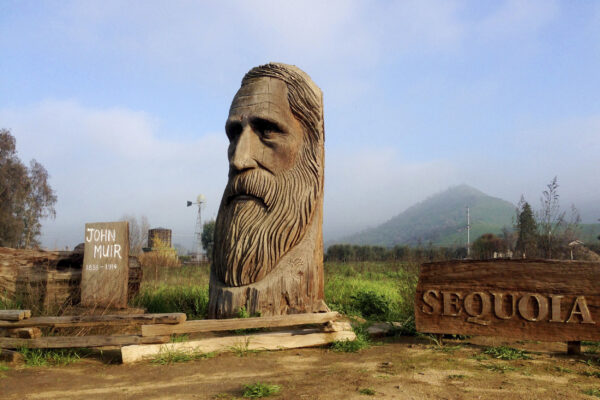

The century-old Sierra Club also was forced to face the music, and in a bigger, more public way — a reckoning that caused their executive director to apologize for decades of the organization’s “whiteness.” As rioters across the nation pulled down statues of former heroes, Sierra Club joined the fray in condemning their own nineteenth-century hero — John Muir — for his association with eugenicists and racists.

Sierra Club Executive Director Michael Brune laid out the nonprofit’s misdeeds in an article published in July, 2020, stating that the original mountaineering club of upper-class white people were only able to enjoy the wilderness they hiked in because “white settlers violently displaced the Indigenous peoples who had lived on and taken care of the land for thousands of years.”

“The whiteness and privilege of our early membership fed into a very dangerous idea—one that’s still circulating today,” Brune added.

Some club members were critical of Brune’s disparagement of Muir. “As a 33-year member of the Sierra Club and a lifelong supporter of equal rights, I have to protest the purity test that you seem to be applying to John Muir and presumably other early members of the organization,” wrote Leo Sutzin. “I think you have to strike a balance in which you note the achievements as well as the sins of current and former members. History brings changes, but to apply tomorrow’s standards to past events and associations—especially events that preceded the civil rights movement—dishonors the organization and its legacy.”

Sierra Club’s reckoning during the political turmoil caused a chain reaction through the organization that caused discord among the volunteer-run organization. After an employee made a public accusation she’d been raped by a volunteer leader, others in the organization were critical of the Club’s decision to dismiss the volunteer without any due process.

Employees also turned to their union for help in what they perceived was racial injustice in the organization. In each chapter, an all-volunteer executive committee is elected by dues-paying members, but even with a democratic election process in place, volunteers in a Colorado chapter complained about disparity of power along gender lines. Elsewhere, tensions have emerged over racial and ethnic dynamics, Alleen Brown reported for The Intercept in August, 2021.

A Lesson for Organizations

After writing “Elephant in the Zoom,” Grim asked Emily Jashinsky, editor at The Federalist, if she was seeing the same culture-war dysfunction in conservative organizations. She responded that she hadn’t seen that.

“But one thing I do see on the right is, a little bit with younger employees in the movement, adopting maybe that mindset that you can sort of weaponize different pathologies or different experiences to mask poor performance, Jashinsky explained. “I don’t see the politicization or the identity stuff so much but I do see a little bit of … victim mentality. People are more likely to try and exploit their role, and the real victims of all that, are the genuine victims of discrimination … because it’s way harder as a manager when you’re listening to all these claims about sexism or bigotry, discrimination in any form, and it’s actually hard to figure out which ones are legitimate.”

There are several lessons to be learned from the dysfunction of progressive organizations right now, and the most important one is that they are based on principles that don’t work. Organizations, in order to be effective, need to be unified in a cause, and the people who work there need to be able to work together, under that unified mission.

Attracting staff who are willing to prioritize the mission over themselves has been a problem, particularly for progressives. Organizations that focus on spotting and attacking problems such as racial injustice are likely to attract staff that will only spot and attack injustice — not out there in the world, but inside their own organization. Bernie Sanders, who waged an energetic grassroots campaign, understood the threat when he told campaign leadership to “stop hiring activists.”

As one executive director told Grim, “I’m now at a point where the first thing I wonder about a job applicant is, ‘How likely is this person to blow up my organization from the inside?’”

In the Guttmacher example, staff members were more concerned about their own power than they were about fulfilling the mission of the institution. And that rendered the institution toothless just in time for the Supreme Court to overturn Roe.

From a higher view, these organizations should be seen as microcosms of the very principles they preach: if an org is dysfunctional in the practice of its principles, you can bet that if practiced in the real world, society would be as dysfunctional as these organizations.

Even though many progressive groups have lost sight of their true mission, distracted by the culture wars, the pendulum is probably already swinging toward reason. The public was fed up with the protests by the end of 2020, and many even avoided watching fall time NBA games because they didn’t want to spend their evening reading the political messages on the athletes’ jerseys.

Black Lives Matter is facing its own reckoning, having become the target of investigations over its finances earlier this year, and Defund the Police, as a movement, has even been condemned by moderate Democrats — most likely due to polling results revealing the public has had enough.

Yet, progressives believe they are fighting for a better world. Some, for a time, will remain blind to the real challenges facing everyday Americans. But more and more, reason will creep back in. Organizations with bad principles will fail, and causes based on correct principles will prevail exactly because they are correct.

– by B.E. Davis

Feature image caption: The 2017 Women’s March, in opposition to Donald Trump’s presidency, was vastly popular among women critical of Trumps misogyny. But within a couple of years, the movement fell apart when their leaders could not unify on inclusion — with disagreements between whites, Blacks and Jews. Courtesy of Bryan Woolston/Reuters.

Read more about where