After a century of ranchers using public lands for grazing, conservation groups are hard at work to strip livestock off the land. Grand Canyon Trust purchased grazing allotments in GSENM but haven’t been able to retire them, and on Monroe Mountain, GCT and Western Watersheds Project seek to reduce cattle on Monroe Mountain for the sake of the aspens.

It was April, 2002, in Arizona, just six years after President Bill Clinton designated 1.7 million acres as the new Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah to the north. Bill Hedden, then-Executive Director of Grand Canyon Trust, found his organization at a major juncture in their campaign to remove cattle from public lands.

Blocking their goal on the front end was a significant problem as legal experts had recently expressed serious doubt on whether GCT’s campaign was legal. But there was a threat from the rear as well: some of the same ranchers who had sold their allotments to GCT, had “filed-over” the very same allotments GCT had just relinquished back to the BLM.

Flagstaff-based Grand Canyon Trust, formed in 1985 as a conservationist group, has long fought to end grazing on the public lands of the Colorado Plateau. But for decades, they and other conservation groups such as Idaho-based Western Watersheds Project have been frustrated with the Bureau of Land Management’s multiple-use doctrine and federal law requiring grazing allotments to actually be used for grazing.

The Idea for a “Grazing Retirement” Program

But then with the creation of GSENM in the vast stretches between Boulder and Kanab, GCT believed that it was now possible to buy grazing allotments from ranchers, and then retire them permanently.

The monument land was still administered by the BLM, which had the mandate to maintain grazing range. But could the land’s new national monument status trump that mandate?

GCT launched its Grazing Retirement Program in the late 1990’s to raise private funds, and had to date, already spent over $1 million to acquire several allotments across the monument, totaling about 120,000 acres. And they had just unconditionally relinquished those allotments to the BLM.

Now the threat that the BLM would be required to permit those relinquished allotment to other ranchers threatened to unwind years of GCT’s efforts — and burn their million-dollar investment.

Grand Canyon Trust was up against a wall, forcing a quick change in strategy. Unwilling to lose control, they would have to retain the permits and use them. On April 15, 2002, GCT wrote to the BLM, withdrawing its previous “offers” to relinquish its grazing preference.

In an ironic twist, the anti-grazing, conservation group Grand Canyon Trust, would become the largest rancher on the Colorado Plateau.

What the Law Requires

In a decades-long fight against grazing on public lands, the retirement of grazing permits was the Holy Grail for anti-grazing groups. But with such a slam-dunk solution not available, conservationists have turned to other ways to fight, to reduce the number of cows through litigation and working to influence land management plans.

Such is the case going on right now for the grazing allotments on Monroe Mountain.

All across the West, ranchers have worked grazing lands since the arrival of the first pioneers in the 1800’s. Many of the families ranching along the Byway are in fact the same families that began ranching those tracts well over 100 years ago.

Taylor Grazing Act

The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 changed how the federal government regulated grazing, and is still one of the most important pieces of legislation establishing and protecting the use of public land for grazing. The law set aside 80 million acres of public land for grazing. Later, the area was doubled to 162 million acres, as part of grazing districts.

The grazing districts are divided into allotments. Federal law requires permit holders to substantially graze these allotments as authorized by their permits. Not only does a permit holder need to make sure the allotment is grazed, but the Department of the Interior also holds that responsibility — meaning that if a permit holder isn’t grazing the land, the DOI needs to find someone who will.

This issue came up shortly after GCT decided to keep its grazing permits. Then-DOI Solicitor William Myers weighed in on whether grazing lands could ever be relieved from grazing, such as through a retirement. In order for grazing to permanently stop, he offered a procedural bar that must be overcome:

There must be a proper finding that lands are no longer chiefly valuable for grazing in order to cease livestock grazing within grazing districts . . . If BLM concludes that the lands still remain chiefly valuable for these purposes, the lands must remain in the grazing district.

Otherwise only Congress had the authority to permanently exclude lands from grazing use.

With all this, it appears that every allotment needs to always be occupied with a permit holder. And livestock.

Loopholes?

So as a “Plan B” strategy, could conservation groups cause the most abusive permit holders to lose their permits?

The Taylor Grazing Act states that permits are issued for a max of 10 years. Current permit holders hold a “preference right” to a renewal, but adds that such a renewal is “in the discretion of the Secretary of the Interior, who shall specify from time to time numbers of stock and seasons of use.” The “discretion” mentioned in the Act is a strong word and could provide a large degree of latitude for land managers to disregard the current permit holder’s first-right to a renewal.

Federal Land Policy and Management Act

The Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) of 1976, however, clarifies what that discretion might be. It explains that an existing permit holder has, not a “preferential right,” but a “first priority” to a renewal only if he complied with the “terms and conditions” of the expiring permit, and also agrees to the terms and conditions of the new permit.

The “terms and conditions” concept, since the FLPMA of 1976, has been used as a big stick to whip ranchers into strict compliance to rules, or in rare circumstances, to pry them out of their allotments. Most of those rules are not specified by Congress per se, but by land managers — who are constantly under the influence of outside interest groups, many of whom are hostile to grazing.

What may have once been a “right” to graze has been eroded with new requirements from environmental legislation and newly-imposed terms and conditions which can effectively be used to make grazing economically difficult for ranchers, and make it all the more easy to disqualify them from a renewal.

Because of this, conservationists and other special interest groups are set up with a powerful weapon to punish ranchers if they choose, and this sets the stage for their outsized involvement in land management planning today. As Piute County Farm Bureau President Trevor Barnson put it, the language of the terms and conditions “and one size fits all range standards have been used by anti-grazing organizations to sue and restrict sound grazing practices and inhibit forest health.”

Aspens on Monroe Mountain

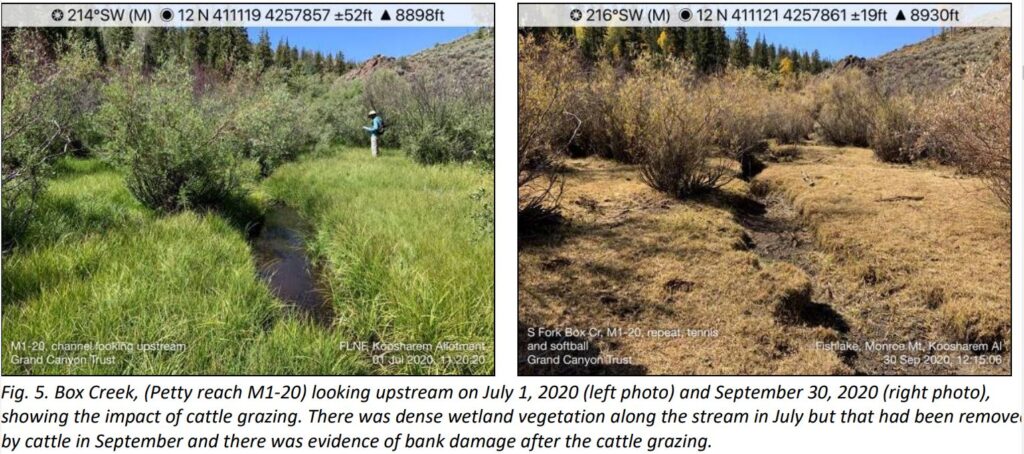

Over the last few years interest in grazing on Monroe Mountain by Western Watersheds Project and Grand Canyon Trust triggered some conservation action. Fishlake National Forest agreed to complete an Environmental Impact Study (EIS) for the allotments on the south end of the Monroe, used to modify future terms and conditions for renewing grazing permits.

The issue conservationists chose as the vehicle to press for grazing changes was the aspen stands.

While aspen stands may seem like a far reach or arbitrary concern for the desert-dwelling Grand Canyon Trust to tackle, aspens have been a valid concern on the Monroe: Tom Tippetts of Utah’s Grazing Improvement Program had estimated that aspens have suffered a 70% decline on the mountain since the introduction of grazing.

Most of that decline was blamed on fire suppression, leaving aspens subject to encroachment of conifers. But ranchers and conservationists argued about whether it was the newly-introduced livestock or the newly-introduced elk that was doing the most damage to regenerating aspen saplings. In order for aspen stands to flourish, they need to continually put up new shoots that won’t immediately get eaten by herbivores.

Response

In response to the blame game Richfield Ranger District of Fishlake National Forest put together the Monroe Mountain Working Group composed of grazing associations, USU Extension, Piute and Sevier County commissioners, state and federal agencies, and conservationists to work on a solution. The working group was lauded as a successful collaboration that aided in the EIS and paved the way for the Monroe Mountain Ecosystems Restoration Project.

With the grazing of 11 allotments containing 2,200 cows and 3,000 sheep over 175,000 acres, a lot was at stake. The working group concluded that the most productive areas for grazing are riparian, followed by aspen stands which shade grasses and forbs for grazing cattle. With a decline in aspen coverage, grazing would be impacted as well.

Meanwhile the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources estimated in 2015 that there were about 1,000 elk on the Monroe.

Elk

Besides the fact that conifers encroach on aspen stands as a forest matures, the single most important factor inhibiting aspen regeneration is the presence of herbivores — grazing ungulates. Ecologists have conducted numerous studies over the last 30 years looking at the link between aspen regeneration and herbivores — specifically, elk.

For instance a 2001 study by Barnett and Stohlgren looked at aspen regeneration over 420 square miles around the National Elk Refuge (Jackson Hole, Wyoming) and found that 44% of aspen stands supported some newer regeneration that had outgrown browsing height, but noted that elk concentration was one of the several important factors limiting aspen regeneration.

Most of the studies focused on the effects of elk rather than livestock because the study areas were forests dominated by elk and native ungulates — such as the National Elk Refuge, Rocky Mountain National Park, and Yellowstone. But some studies sought to distinguish the effect on aspen stands between big game and cattle.

The Difference Between Big Game and Cattle

A 2013 study by Bork and Carlyle, et al., monitored aspen saplings in Canada’s aspen parkland, which is the 1,000-mile stretch of aspens on the Great Plains’ northern border. In separate paddocks (with about 8% aspen coverage), the study found that elk browsed the aspen saplings the most, followed by bison and then deer. They also noted that cattle browsing aspen was negligible — or rather, insignificant.

A 2014 study by Walker, Anderson and Fugal also found that big game had a bigger impact on aspen suckers than cattle. In that study, researchers fenced off four areas inside a recently-burned aspen stand: one with cattle, one with big game, one with both cattle and big game, and the fourth had none.

What was helpful in Walker’s study is that after watching the four plots for several years, the “control” plot (with no herbivores in it) had aspen coverage of 34%. The cattle plot took second place at 31%, followed by 25% in the big game plot. But the plot shared by both big game and cattle had been mowed down to a mere 4%. The study concluded that there was little difference in aspen regeneration between the cattle plot and the no-use plot, and also recommended that after prescribed burns of aspen stands, the number of total herbivores should be reduced to allow suckers to develop beyond browsing height.

Fire

Other studies also discussed the role of fire in aspen regeneration. Aspens are very effective at sending up suckers after a fire, and historically, fire has been the most important factor in aspen regeneration. But with the introduction of both cattle and large game such as elk in the mountains of Central Utah, these regenerating aspen stands now have to compete with hungry herbivores.

Because of this, several studies concluded large-scale fires were a benefit. Small, prescribed burns do nothing more than create “candy stands” of young aspen shoots for big game to eat, while large-scale fires produced so many acres of aspen shoots that the population could not be overwhelmed by herbivores.

In the Bitterroot Mountain on the border of Idaho and Montana, for instance, large-scale fires across the range before 2000 substantially increased the amount of aspen coverage. “The Bitterroot is not known for having a lot of aspen,” said Bitterroot silviculturist Sue Macmeeken, noting there were very few, mostly small stands and single trees among the conifers before that time. But she said after the fires that “there is so much of it that it appears that there’s plenty for the deer & elk to munch on and we really didn’t notice it disappearing anywhere.”

Butting Heads

In spite of a successful collaboration between interests as part of the Monroe Mountain Working Group, the new fight over the last couple of years has been to influence the actual drafting of Fishlake’s land management plan, and more specifically, what terms and conditions grazing permit holders should agree to.

Fishlake National Forest published its proposed action for the EIS, which would authorize the continued grazing on the six allotments in the Monroe’s southern half. Fishlake began accepting public comments in 2020.

During the initial public comment period, about 60 comments had been submitted. Of the comments, 22 stated they were local ranchers or actual permit holders on Monroe Mountain.

Comments Opposed to Grazing

Seventeen comments were either opposed to, or critical of the plan to allow grazing. Of those opposed, 11 urged the Forest Service to adopt the “Climate-Conscious Alternative” plan, which had been drafted by Western Watersheds Project and Grand Canyon Trust.

Interestingly, of the 11 who urged Fishlake to adopt GCT’s Alternative in its entirety, eight of them were college students who had volunteered in a field internship project lead by GCT’s Forests Program Director, Mary O-Brien. Verbiage in the students’ comments suggests they had received the same coaching in writing their comments.

Comments in Favor

While people opposed to grazing focused their comments toward cows’ impact on aspen regeneration and climate change, the rancher group discussed more on-the-ground issues such as water improvements, fencing, positive economic effects of grazing, and worries about influence from “special interest groups.” And the biggest problem they brought up was the elk.

Ranchers praised efforts to regenerate aspens, but unlike the conservation crowd, ranchers only incidentally mentioned ongoing efforts rather than urging Fishlake to change its plans on aspens.

Because it wasn’t available until late, none of the ranchers mentioned GCT’s “Climate-Conscious Alternative” plan, which is problematic. Any time a special interest is willing to write actual rules and urge a government agency to adopt those rules entirely, those opposed need to pay attention. Especially those who will be subject to those rules.

This is the case for Monroe Mountain ranchers: GCT has offered to write the rules that will be imposed on the ranchers.

GCT’s efforts to actually offer language outlining rules is helpful to the Forest Service. But for the ranchers who often see GCT’s objectives as directly opposed to their own, they should be as wary as a homeowner who hires a burglar to design his home’s security system.

As an example the Alternative would prevent the Forest Service from considering economics of ranching operations in a response to utilization exceedances, and — a clause akin to their Holy Grail — long-term conservation non-use would be allowed without affecting retention of the permit. Ranchers need to ask, why would a conservation group ask for these things?

Conclusion

While ranchers are surviving in their day-to-day work on the ground, conservation groups are fighting a long-term, high-level battle to reduce or eliminate grazing on public lands. Their work is thorough, and careful. They understand the laws, and hire attorneys to help them strategize how to achieve their objectives. They are also well-funded compared to ranchers.

On Monroe Mountain the issue of choice for conservationists was aspen stands, but aspens are the smallest part of why conservationists are opposed to grazing. Aspens is just the argument that worked for Monroe Mountain. But while conservationists used the aspens to justify reduction of livestock grazing there, ranchers hardly countered this. They did not address the issue head-on, meaning that the two sides may still be talking past each other.

How Do People Make a Living as Ranchers?

In GSENM two decades ago the issue of choice for Grand Canyon Trust was the effect of drought on ranching economics. In the quest to buy allotments for the sake of retiring them, GCT’s Director Bill Hedden expressed his frustration to the New York Times in 2005 saying how he couldn’t understand how people could make a living as ranchers. “We’ve been out there dealing with this,” he said. “We solved the problems of the BLM, and [ranchers say] we’re hurting the Kane County economy by buying out guys who are going bankrupt? I don’t get it.”

But comments from ranchers show there is more to ranching than mere economics. It is a lifestyle, and to some, it is a good way to manage the land and put it to good use. In their minds, the ranchers are the real stewards of the land, qualified by the fact they care for it more than anyone.

To date the multiple-use doctrine of most of the nation’s public land is on the side of the ranchers. But with the tide of public opinion growing cold on grazing, coupled with the incessant efforts of well-funded conservation groups, ranchers had better keep an eye.

– The Byway

Feature image caption: Cows graze on Tenmile Flat south of Escalante, February 24, 2022.

Read more about the sharing of public lands in Join the Dialogue on Managing Local Public Lands.